|

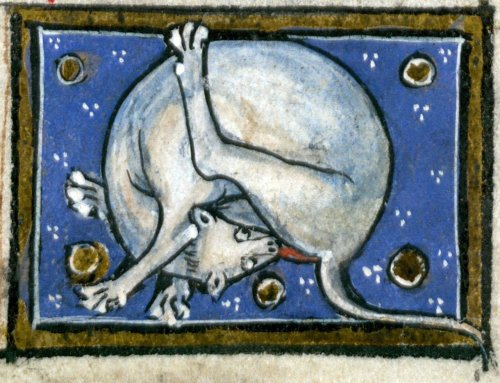

Before getting to the tale of Pangur Ban, let me relate to you a

description of cats given by Bartolomaeus Anglicus (Bartholomew the

Englishman), a 13th c. Franciscan monk and encyclopedist who wrote the

19-volume De Proprietatibus Rerum (On the Properties of

Things), an exhaustive work on theology, medicine, the natural

sciences, and geography, some time before A.D. 1260. He wrote that cats

are

... a beast of

uncertain hair and color. For some cat is white, some red, and some

black, some calico and speckled in the feet and in the ears... And hath

a great mouth and saw teeth and sharp and long tongue and pliant, thin,

and subtle. And lappeth therewith when he drinketh... And he is a full

lecherous in youth, swift, pliant and merry, and leapeth and rusheth on

everything that is before him and is led by a straw, and playeth

therewith; and is a right heavy beast in age and full sleepy, and lieth

slyly in wait for mice and is aware where they be more by smell than by

sight, and hunteth and rusheth on them in privy places. And when he

taketh a mouse, he playeth therewith, and eateth him after the play.

And is as it were wild, and goeth about in time of generation. Among

cats in time of love is hard fighting for wives, and one scratcheth and

rendeth the other grieviously with biting and with claws. And he maketh

a ruthful noise and ghastful, when one proffereth to fight with one

another, and unneth is hurt when he is thrown from a high place. And is

a cruel beast when he is wild and runneth in woods and hunteth the

small wild beasts... And falleth on his own feet when he falleth out of

high place... And when he hath a fair skin, he is as it were proud

thereof, and goeth fast about. And when his skin is burnt, then he

bideth at home. And is oft for his fair skin taken of the skinner, and

slain and flayed.

"Among cats in

time of love is hard fighting for wives," "And when he hath a fair

skin, he is as it were proud thereof, and goeth fast about" --

brilliant! And while we're on the general topic of the cat in the

medieval world, heed this sage advice from the so-called "Distaff

Gospels," a compendium of late 15th c. French "old wives tales"

recounted as conversations between women sitting around together on

long Winter nights. On the second night, the women say:

When you see a

cat sitting in the sun in a window, licking her behind and not rubbing

her ear with her leg, be sure that it will rain that very day...

..Lady Mehault Caillotte got up and said that it is true; indeed her

washing is still in the laundry vat, and she dares not wash it because

her cat does not stop licking her behind.

What an

unfortunate mish-mash of personal pronouns! But what a great excuse for

not doing the laundry: "Dear, I couldn't possibly do the laundry today;

I saw Tiddles licking her butt!"

And there is more cat-wisdom to be

learned; on the fifth night, the women say:

A woman who does

not want to lose a good cat, if she has one, must rub the four legs

with butter for three nights, and the cat will never leave the house.

"Good cat"? Ha!

Rotten to the core, the lot of them -- but we love them anyway!

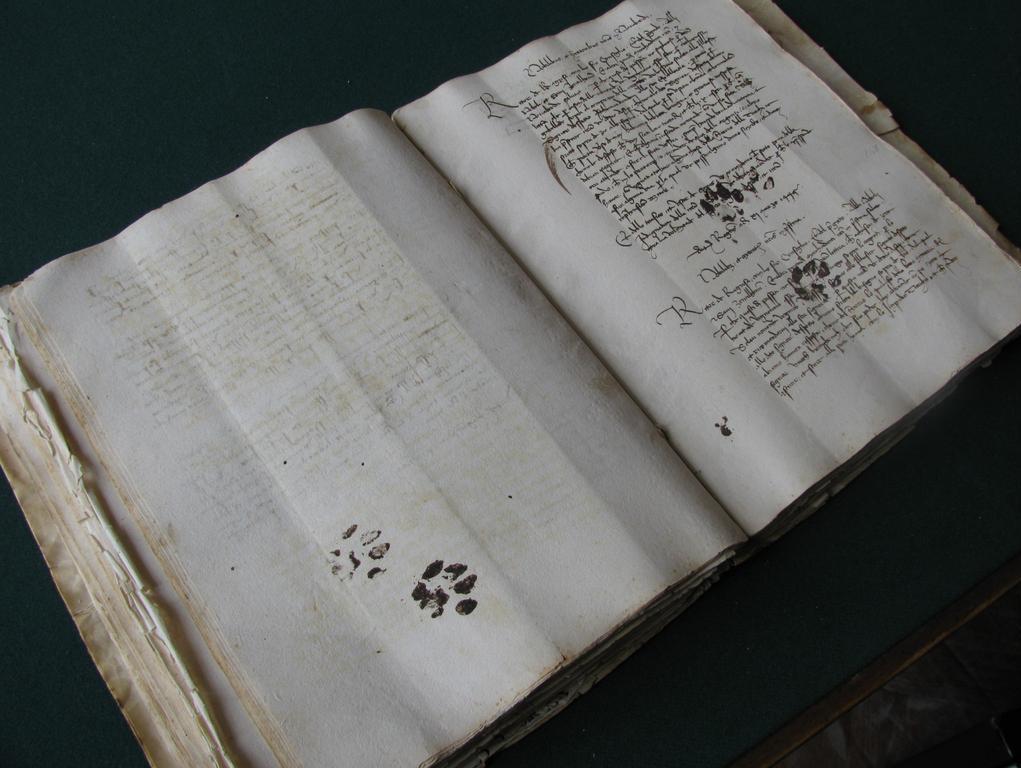

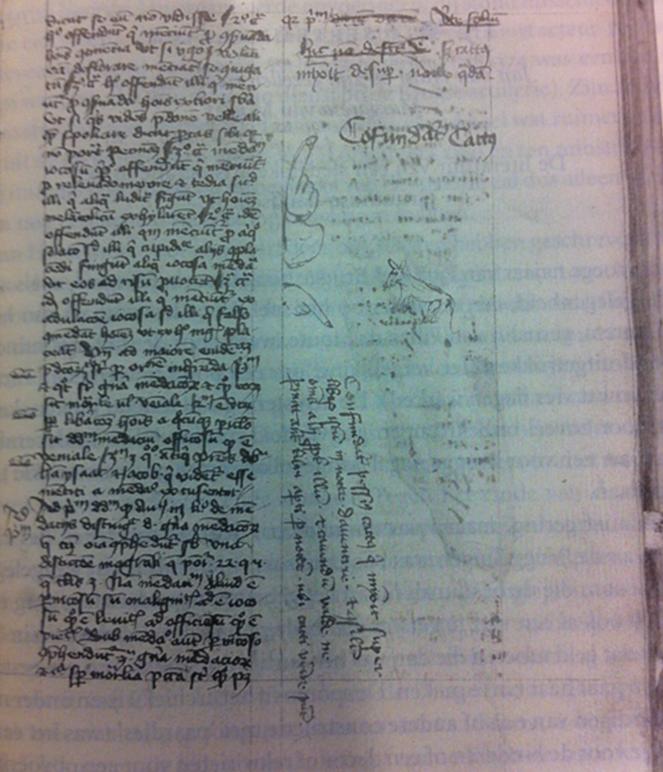

Would you like to see a 15th century manuscript that got

walked on by a

medieval cat -- who left his inky pawprints all over it? Below, click

the

picture

on the left to enlarge. Click the picture to the right to see a

manuscript written in Deventer, Netherlands in 1420 -- and which has a

large empty

spot where a cat had peed on the page, forcing the scribe to write

around it.

He left a curse on the kitty, and all cats, which reads:

“Hic non

defectus est, sed cattus minxit desuper nocte quadam. Confundatur

pessimus cattus qui minxit super librum ostum in nocte Daventrie, et

consimiliter omnes alii propter illum. Et cavendum valde ne

permittantur libri aperti per noctem uni cattie venire possunt.”

("Here

is nothing missing, but a cat urinated on this during a certain night.

Cursed be the pesty cat that urinated over this book during the night

in Deventer and because of it many others too. And beware well not to

leave open books at night where cats can come.")

But let's end this digression and move on to the absolutely

delightful

poem, Pangur Ban. It was written in the 8th or 9th century, on a 4-page

manuscript (see picture at the bottom of the page) by an anonymous

Irish Benedictine monk who lived in the extant St. Paul's Monastery on

Reichenau Island in Lake Constance (Bodensee), where Germany meets with

Austria. Imagine the monk at night in his candlelit cell,

delving into Sacred Scripture's eternal Truths, together and happy with

his kitty, who went about his own business. Little did he know that

1,200 years later, others would fall in love with Pangur Ban, too.

Pangur Ban

I and Pangur Ban my cat,

Tis a like task we are at:

Hunting mice is his delight,

Hunting words I sit all night.

Better far than praise of men

Tis to sit with book and pen;

Pangur bears me no ill will,

He too plies his simple skill.

Tis a merry thing to see

At our tasks how glad are we,

When at home we sit and find

Entertainment to our mind.

Oftentimes a mouse will stray

In the hero Pangur's way;

Oftentimes my keen thought set

Takes a meaning in its net.

'Gainst the wall he sets his eye

Full and fierce and sharp and sly;

'Gainst the wall of knowledge I

All my little wisdom try.

When a mouse darts from its den

O how glad is Pangur then!

O what gladness do I prove

When I solve the doubts I love!

So in peace our tasks we ply,

Pangur Ban, my cat, and I;

In our arts we find our bliss,

I have mine and he has his.

Practice every day has made

Pangur perfect in his trade;

I get wisdom day and night

Turning darkness into light.

And here it is in the original language for you scholars out there:

Pangur Ban

Messe ocus Pangur B�n,

cechtar nathar fria saindan:

b�th a menmasam fri seilgg,

mu memna c�in im saincheirdd.

Caraimse fos (ferr cach clu)

oc mu lebran, leir ingnu;

ni foirmtech frimm Pangur B�n:

caraid cesin a maccd�n.

O ru biam (sc�l cen sc�s)

innar tegdais, ar n-oend�s,

taithiunn, dichrichide clius,

ni fris tarddam ar n-�thius.

Gn�th, huaraib, ar gressaib gal

glenaid luch inna l�nsam;

os m�, du-fuit im l�n ch�in

dliged ndoraid cu ndronch�ill.

Fuachaidsem fri frega f�l

a rosc, a ngl�se coml�n;

fuachimm chein fri fegi fis

mu rosc reil, cesu imdis.

Faelidsem cu ndene dul

hi nglen luch inna gerchrub;

hi tucu cheist ndoraid ndil

os me chene am faelid.

Cia beimmi a-min nach r�

ni derban c�ch a chele:

maith la cechtar n�r a d�n;

subaigthius a �enur�n.

He fesin as choimsid d�u

in muid du-ngni cach oenl�u;

du thabairt doraid du gl�

for mu mud cein am messe.

The Reichenau Primer which contains the poem

|

|